Hugo Is Not a Rap Album: It's a Reconciliation

With Hugo, Carner solidified his voice as a leading figure in confessional hip-hop, intimate, introspective, and deeply human.

For my first post, I wanted to spotlight an artist who’s mastered the art of vulnerability in Hip-Hop. If you're new to the genre or looking for an album that feels like a conversation with your closest friend, then Hugo by Loyle Carner is where you should start. Here is why this album is a modern classic.

Vulnerability, grief, and identity unfold in Hugo, a quiet devastation ascending Carner into the emotionally articulate lineage of confessional hip-hop, alongside artists like Little Simz, Dave, and Kendrick Lamar.

The album weaves itself into the central motif of fatherhood, presented in three powerful forms:

The grief of losing his Step-father and how that deeply impacted his musical career.

The reconciliation with his biological father, who taught him to drive in a car affectionately nicknamed ‘HUGO’ during lockdown.

His journey of becoming a father, marked with love and growth, with the acceptance that it hasn’t been perfect.

Each song on Hugo feels like a chapter in Carner’s own story. Below, I will dive into key tracks which showcase the poetic depth which cements Carner into an auteur for his genre.

Hate

“Let me tell you what I hate

Everything I ain't

Everything I done

Everything I break”

The song is the pinnacle of frustration, with Carner openly admitting it’s one of the few he’s made from a bad place. It reflects Carner’s experiences around being black today, feeling overwhelmed with blatant racism and microaggressions faced in his life. ‘Hate’ opens the gates to Carner’s self-doubt and worth as he grapples with his flaws and insecurities, making it a raw, unfiltered confession, alongside moody beats and introspective lyricism.

“I fear him

Yeah, I fear the colour of my skin

I fear the colour of my kin

I still feel the colour that's within”

The vulnerability Carner places into this song pays off as what we are left with is pure emotion, unfiltered and angry, as the speaker attempts to have an open, honest conversation. His words aren’t there to impress, but begging the listener to hear him, setting the emotional foundation for Hugo and signalling the album will be: a deeply human and uncomfortable journey, with themes of identity, grief, and growth.

Georgetown

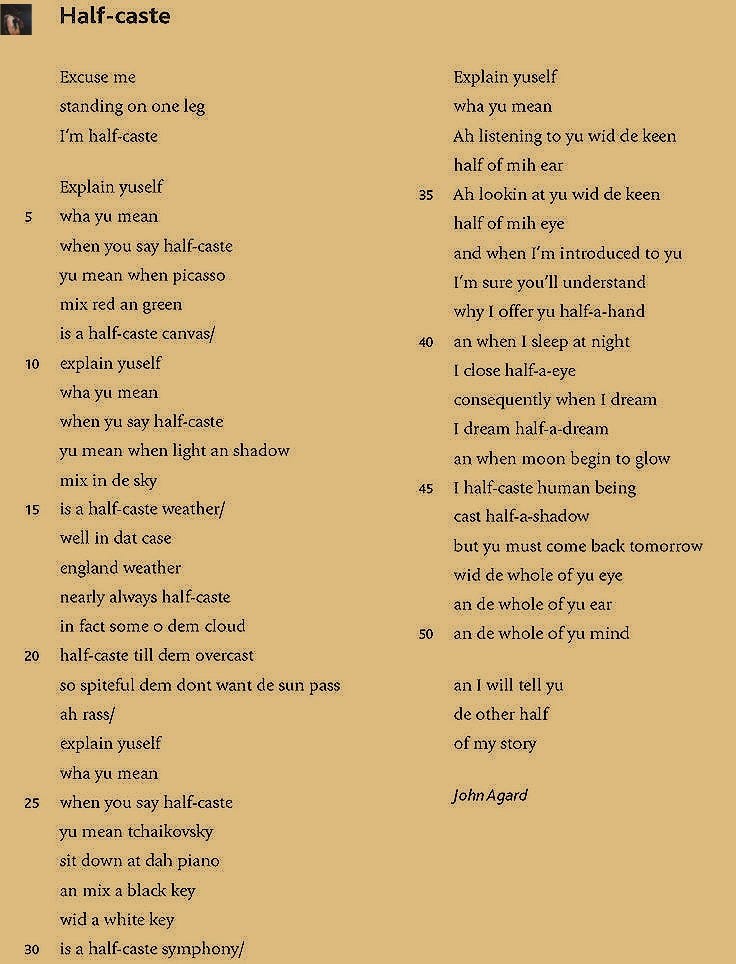

“I half-caste human being”

Listen to this song if you want to know who Loyle Carner is. Unapologetically Black-British, Carner uses the prose of John Agard, a prominent voice in British literature, to explain who he is, embracing the complexity and duality of having two heritages, whilst disregarding that he is Half anything, exerting his existence confidently.

“Yeah, I'm black like the key on the piano

White like the keys on the piano, low ammo

Uh, black like the key on the piano

White like the key on the piano”

This short, punchy chorus, is a phrase which demands space, space for both sides of his British, Guyanese heritage with it being a spin on Agard’s own words, transforming it for modern audiences, and highlighting how fundamental the message is for modern audiences, with the track coming across as a conversation across generation: the voice of Black Brits refusing be defined by fractions.

Musically, ‘Georgetown’ is stripped down to allow Carner’s lyricism and delivery to spotlight, and unlike the more vulnerable tracks on the album, his flow is confident, allowing his statement to be heard, with the track being assertive. Carner knows who he is, confronting his identity head-on, with ‘Georgetown’ offering rare reason and affirmation, strengthening the beauty of duality for the album.

Blood on my Nikes

Defiant. This word perfectly sums up the genius which is ‘Blood on my Nikes’. The song is a journey from Carner’s youthful acceptance of the normalised violence which surrounded his earlier years, to understanding that there is a means for change, not wanting his son to live in a world which accepts it so easily.

“When they took the boy's life 'cause he's from the wrong side

Shit, I know I should have thought twice

Ah, washing off the blood from my Nikes”

These lyrics in particular paint a powerful picture of how visible the knife crime epidemic is in the UK, with the ‘Postcode wars’ being all too familiar to Carner, having grown up in London. The lyricism in this song confronts the harrowing epidemic, with Carner developing this track into a powerful reminder of the cost of survival, and the Grief tied to the senseless loss of young lives.

“As knife crime claims more lives within our country

Never has so much been lost by so many

Because of the indecision of so few”

The call for action is apparent at the end of the song. A speech made by Athian Atec, a powerful voice, representing the youth, and cementing this song into a protest, crying out for the government to approach the knife crime epidemic through compassion and accountability, cementing the track as one of Hugo’s most urgent and emotionally charged moments.

HGU

A mantra of reconciliation, not just of others, but of oneself. ‘HGU’, the last three letters of Carner’s biological father’s license plate, with the song being about Carner attempting to forgive his father for abandoning him, with it being the perfect conclusion as to why this album was created.

“Yeah, I forgive you, I forgive you, I forgive you”

The first sentence of the song demonstrates how forgiveness isn’t a neat, clean resolution. It’s messy, fraught with hesitation, and deeply human- a struggle which Carner documents throughout the track, with even the instrumental telling a story of forgiveness. The song begins with loud, urgent drums that capture the raw tension of forgiveness. Gradually, the drums fade, leaving only a soft, delicate piano. By the end, it’s just the piano—creating a quiet, vulnerable space that reflects the fragile, introspective nature of reconciliation.

Understand the reasons that you're sinful 'cause Earth's evil

Yeah, 'cause hurt people, hurt people

Especially the ones who weren't equal, the burnt treacle

Through Carner’s attempt to forgive, he tries to look at the world through his biological father’s eyes, acknowledging that abuse is a cycle, and as his father is black, this abuse has been amplified. This acknowledgement of “hurt people, hurt people” reveals Carner’s growing understanding that pain and trauma are often inherited, not easily escaped. Forgiveness here is less about absolution and more about empathy: recognising the flawed humanity in his father’s actions while grappling with his wounds. It’s a raw, honest confrontation with intergenerational trauma and the complexities of identity and love.

By holding space for this complexity, HGU doesn’t offer easy answers but instead invites listeners into the messy, difficult process of healing, one that’s ongoing and imperfect.

CONCLUSION:

Overall, Hugo is much more than a rap album; it is a deeply personal reconciliation. Through raw vulnerability and honest storytelling, Loyle Carner invites us into his journey of grief, identity, and forgiveness. It’s an album that refuses to shy away from the complexities of fatherhood, trauma, and systemic challenges, offering no easy answers but a space for reflection and healing.

Listening to Hugo feels like being part of a conversation that’s both intimate and urgent, reminding us that reconciliation with others and ourselves is a continuous, messy, and necessary process. Whether you’re a longtime hip-hop fan or new to the genre, Hugo challenges us to rethink what rap can be: not just a soundtrack, but a path toward understanding, empathy, and ultimately, peace.

Overall rating 5/5

Thank you for reading LowFidelityFaith.

If you enjoy my content, please subscribe. I will be uploading every month, and will review all requests.